Descovy for PrEP …excluding cisgender women

Earlier this month the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a statement approving the use of Descovy for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) to prevent infection with HIV. This announcement shockingly excluded cisgender women. Descovy is only the second drug approved for HIV prevention alongside its better-known counterpart Truvada which has been approved for this purpose since 2012. The news was received with shock by HIV/AIDS advocates and the medical community at large. The drug’s maker Gilead, only tested its efficacy in men and transgender women, and as such the US F.D.A claimed that a recommendation could not be made for its use in cisgender women/individuals engaging in receptive vaginal sex.

This announcement highlights a pattern in which women are excluded in important studies of new medications and interventions targeting HIV prevention and treatment. UNAIDS set at ambitious target to end the AIDS epidemic by 2020 called 90-90-90. This means 90% of all people living with HIV(PLWH) will know their HIV status, 90% of all people with diagnosed HIV infection will receive sustained antiretroviral therapy and 90% of all people receiving antiretroviral therapy will have viral suppression. While many have lauded this aggressive push towards ending the epidemic, we are far from achieving this goal which will remain unattainable if women continue to be excluded in important studies on treatment, prevention and potential cure strategies for HIV.

Unique Challenges and Pattern of Neglect

Women represent half of the adults living with HIV worldwide and 70% of PLWH in sub-Saharan Africa. HIV and AIDS remain the leading cause of death in women of reproductive age and infection rates in young women aged 15-24 are twice as high as in young men of the same age group. Despite these stark numbers, women are severely under-represented in clinical trials on HIV treatment and prevention – accounting only for about 19% of participants.

This pattern unfortunately is not new because including women in HIV clinical trials presents unique challenges that researchers have historically not been equipped or prepared to fully address. Women of reproductive age can become pregnant which in itself becomes a barrier to entering certain clinical trials. Furthermore, women often bear most of the responsibilities of childcare and other family related commitments. Disadvantaged women living in poverty, adolescent women and women living sub-saharan Africa represent vulnerable groups disproportionately affected by these factors. This implies that they are more likely to miss follow-up visits required by clinical trials and to drop out of studies before completion even when they are included.

This has resulted in limited information on the safety of most HIV drugs in pregnancy and a limited understanding of how gender specific physiologic and genetic factors may affect the body’s immune response to the virus. The most significant implication of this in my view is we may be failing to offer women the best data proven interventions for HIV prevention and treatment targeted to their unique needs.

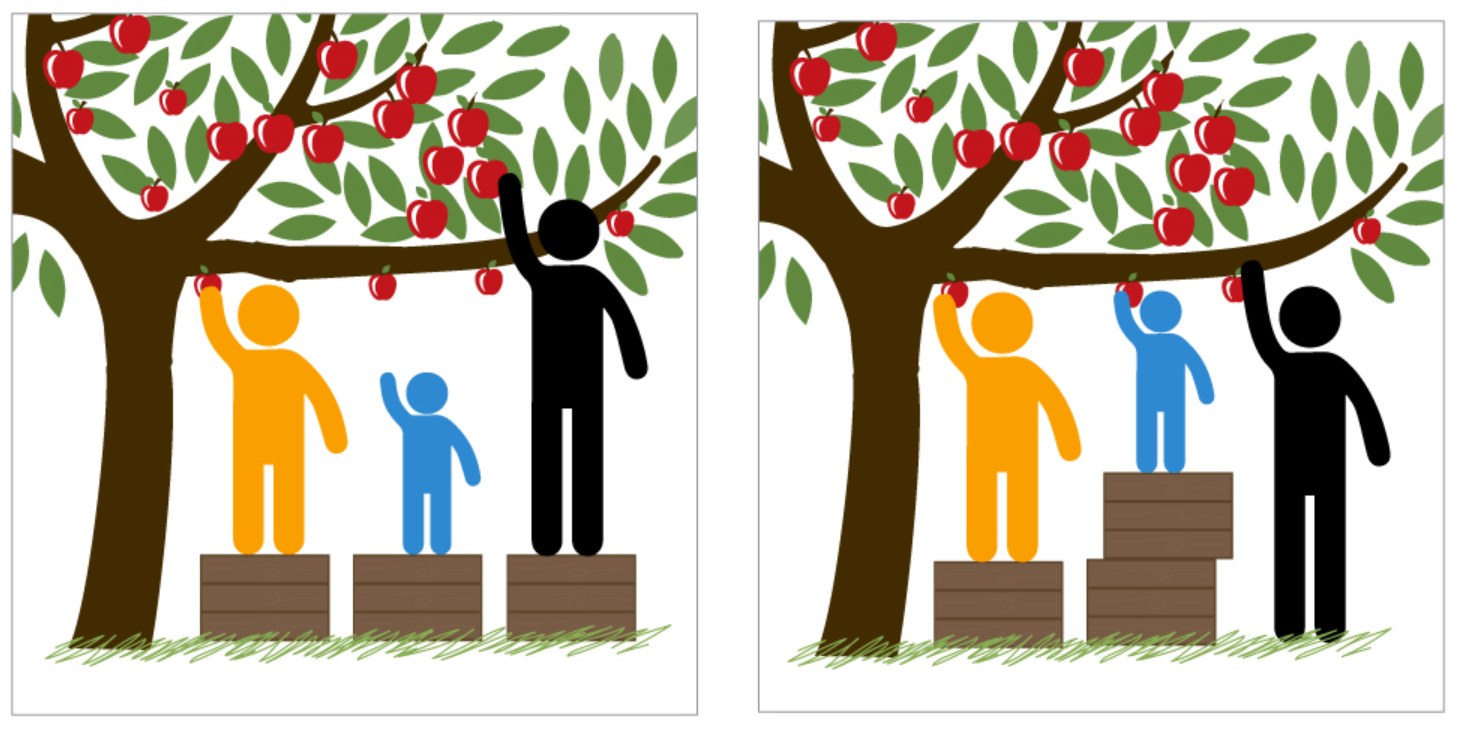

Equity and Access

In addition to the unique challenges of HIV research in women, there are also significant barriers and challenges to accessing those interventions which have proven to be beneficial. A good illustration of this are the challenges faced by the roll-out of the potent antiretroviral agent Dolutegravir, for women of childbearing age in sub-Saharan Africa.

Compared to older antiretroviral drugs, Dolutegravir controls HIV more rapidly and is associated with fewer side effects. In 2017 a generic one pill a day antiretroviral cocktail of three drugs including Dolutegravir became available for just 75$ for a year’s worth of treatment. This development meant that millions of PLWH in Sub-Saharan could finally have access to a state of the art first line treatment for HIV at a cost that was more affordable than the older less well tolerated drugs.

Dolutegravir and the Right to Choose

In May of 2018, just as governments in the region were planning on including Dolutegravir into national treatment guidelines, a study in Botswana reported some concerning findings. Among 596 children born to women with HIV who received Dolutegravir during the first trimester of pregnancy, they noted an increased number of children born with neural tube defects (0.7%) compared to women who received older antiretroviral drugs (0.1%). A larger study presented at the IAS (International AIDS society) meeting in June 2019 estimated an associated risk for neural tube defects of about 0.4% with Dolutegravir but conceded that more data is needed.

These concerns surrounding the use of Dolutegravir in pregnancy slowed its rollout with many governments debating whether women of reproductive age living with HIV should be given access to this drug. This led to a powerful consensus statement by female HIV activists in the region stating “Each woman, is not just a vessel for a baby, but an individual in her own right, who deserves access to the very best evidence-based treatment available and the right to be adequately informed to make a choice that she feels is best for her.”

A simple solution to ensuring that women can safely access and benefit from Dolutegravir while we await more definitive information on its safety in pregnancy, is providing women with HIV access to contraception and pregnancy termination services. This in itself is fraught with controversy and opens the broader conversation of how a woman’s right to choose what happens to her body and her health is inextricably linked to our ability to fully address the HIV epidemic in this demographic.

On the issue of PrEP Access and Women

Pre-exposure prophylaxis with a combination of two antiretroviral drugs in a single pill, is the only effective strategy proven to prevent HIV infection. The roll-out of this intervention is unfortunately another area in which women have experienced unequal attention. In the United States besides black, hispanic and white MSM (men who have sex with men), black women are the largest group at risk for HIV infection. In 2017, 4008 new HIV infections in the United States occurred in black women yet many have never heard of PrEP or how to access it.

From a broader perspective about 1.1million Americans are at high risk for HIV and could benefit from PrEP according to the CDC . However only about 10,000 women of any race are using the pill to prevent HIV. Excluding women from access to the latest drug (Descovy) approved from PrEP only compounds these existing inequities.

Young women in sub-Saharan Africa represent 3 million of the 4 million PLWH aged 15-26 years in the region. Ongoing studies on PrEP usage in this vulnerable group indicate that while many (95%) are willing to take PrEP, sustained adherence to the intervention is a challenge. Only 9% of young women are shown to have drug levels in their blood associated with high adherence at 12 months after being enrolled into PreP programs. This suggest that young women in Sub-Sharan Africa may have unique PrEP adherence support needs which would need to be studied and addressed in order to fully utilize this prevention strategy.

Leave no Woman Behind

I am currently taking care of Anna in a clinic in Atlanta. She is a 30-year-old black woman who was recently diagnosed with HIV and AIDS during her pregnancy earlier this year. Fortunately, her baby was born healthy but Anna is fighting for her life after presenting with very advanced disease and several complications. During her most recent visit to the clinic, I prepared a pill tray with the 15 pills a day she is expected to take to treat the multiple infections ravaging her body and to control the HIV.

Before coming to the clinic, Anna had never heard about PrEP and did not have access affordable birth control. She is often teary with worry that she will not survive this phase and may not live to see her children grow up. This is what being left behind looks like – missed opportunities for prevention, late diagnoses and complications of AIDS.

Every minute around the world, more than two women will become newly infected with HIV and one of those will be under 18. This will only change if we are more deliberate in prioritizing HIV research that includes women. Getting to zero, means leaving no one behind. When it comes to women and HIV epidemic, we are doing just that.

*Names and specific patient identifiers were modified for this article to preserve patient anonymity.

*Access outbound links to references by clicking on the underlined text.

Written by: Boghuma K Titanji