A new long-acting option for HIV PrEP

On Thursday, June 20, 2024, Gilead released the highly anticipated topline results of the PURPOSE-1 trial. This phase three randomized controlled trial demonstrated that a twice-yearly subcutaneous injection of the antiretroviral drug Lenacapavir was 100% effective in preventing HIV infection. This is in compared to the once-daily oral pill of Descovy (which contains tenofovir alafenamide and emtricitabine) or Truvada (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine). Although these results have not yet been peer-reviewed, they are truly groundbreaking and mark a pivotal moment in HIV prevention.

The study, conducted in Uganda and South Africa, included 5,300 cisgender women and adolescent girls aged 16-25. It is the first-time initial results for a novel agent for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) comes from a study including cisgender women. Historically, available options for HIV PrEP were initially studied among men who have sex with men (MSM), with studies in cisgender women, particularly in Africa, lagging several years behind.

The trial Results:

Despite a decade of PrEP, barriers to access persist

It has been 12 years since the Food and Drug Administration approved the first combination drug, Truvada, for use as PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis). In the absence of an HIV vaccine, PrEP has been transformative in the fight against the HIV epidemic, offering people the option to live and love without the fear of acquiring HIV. However, despite its promise, oral PrEP which now includes Truvada and Descovy, has not fully lived up to its fullest potential. Many populations that could benefit from it continue to struggle with awareness about the intervention and ways to access it.

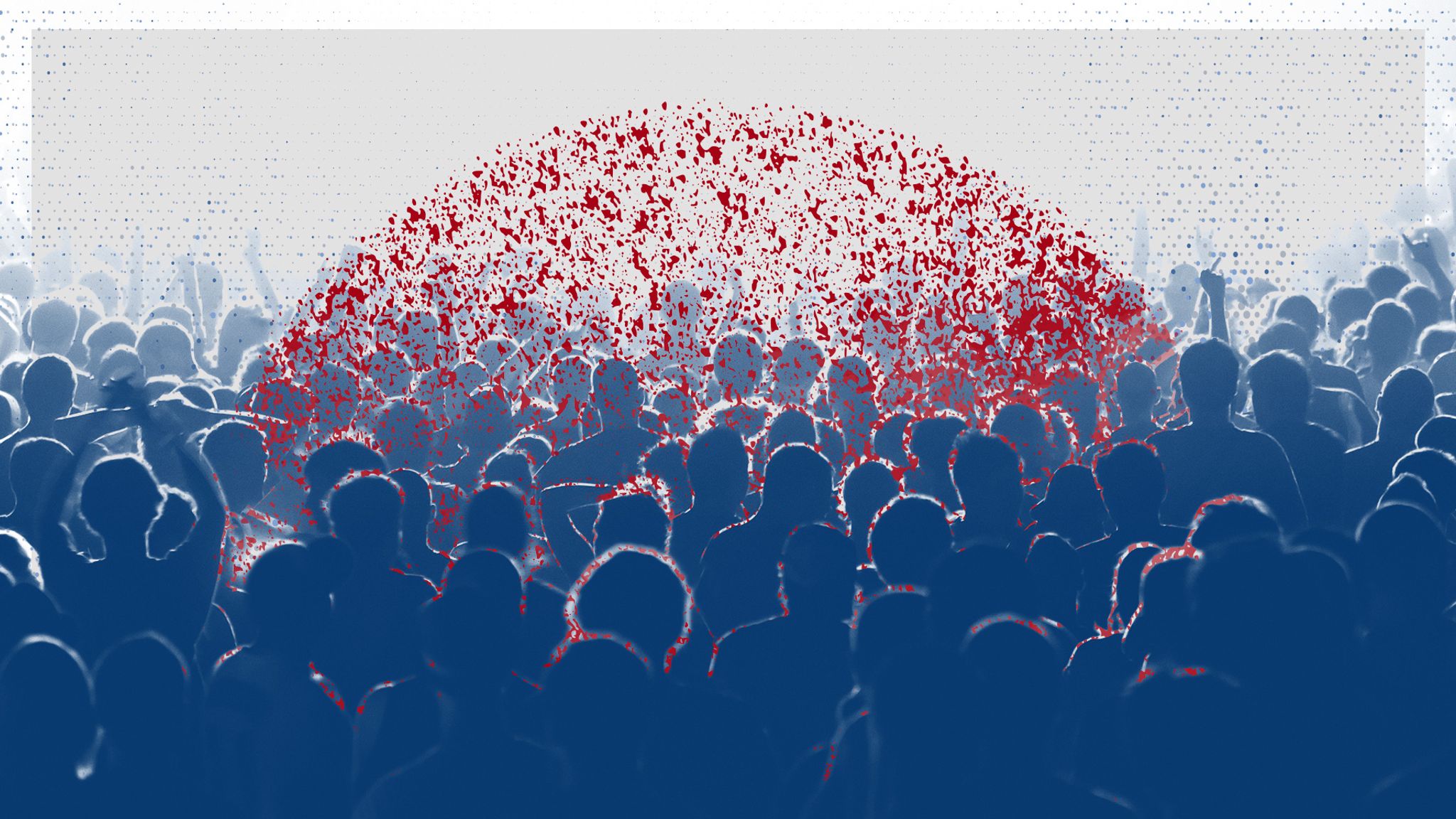

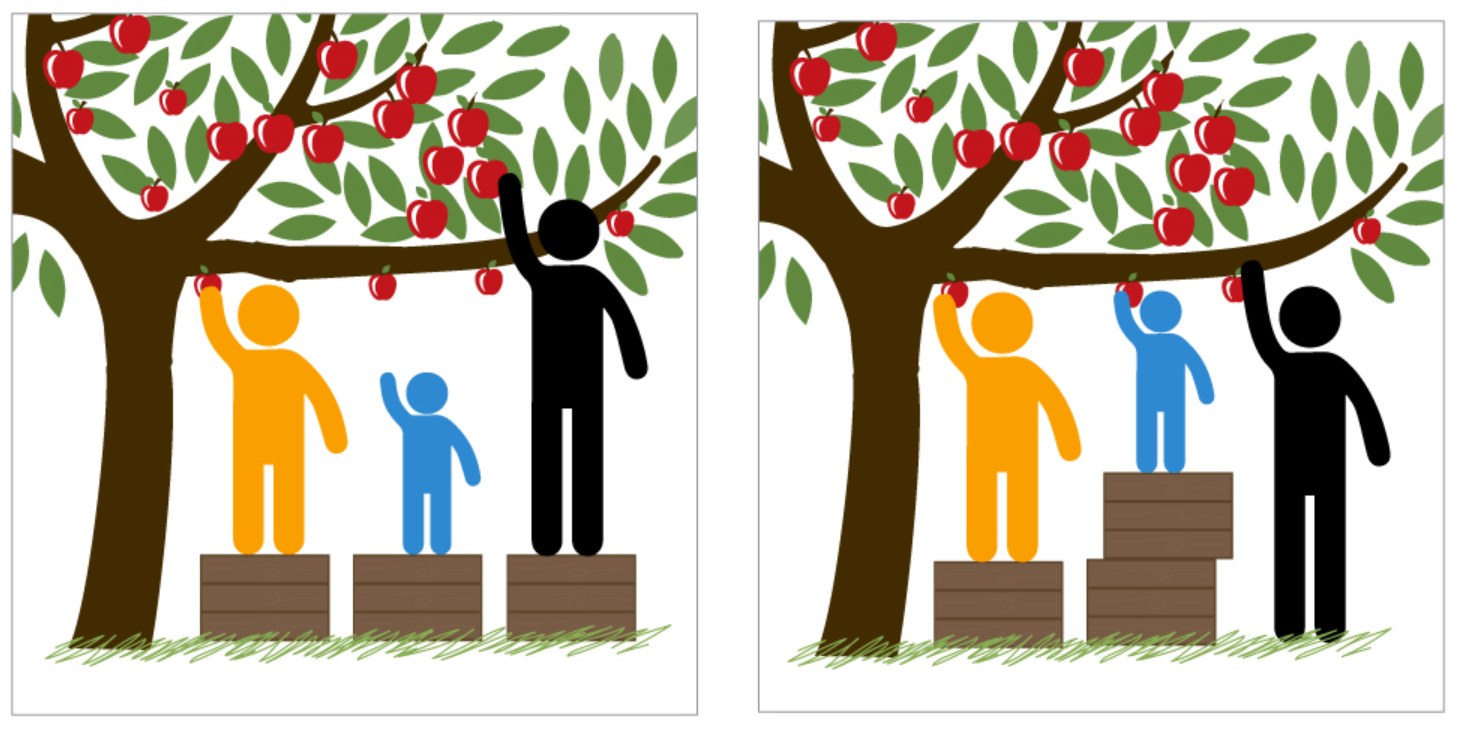

For example, in the United States, Black women accounted for 54% of new HIV infections in women in 2021, yet only 2% of the estimated 468,000 Black women who could benefit from PrEP receive a prescription for it. This disparity is partly due to a lack of awareness about the benefits of HIV PrEP, the prohibitive cost of accessing the intervention in some States, and the absence of messaging that addresses the unique needs of this group. Stark disparities also exist across racial groups. The CDC estimates that while 94% of White people who could benefit from PrEP have been prescribed the intervention, only 13% of Black and 24% of Hispanic/Latino people who could benefit have been prescribed PrEP.

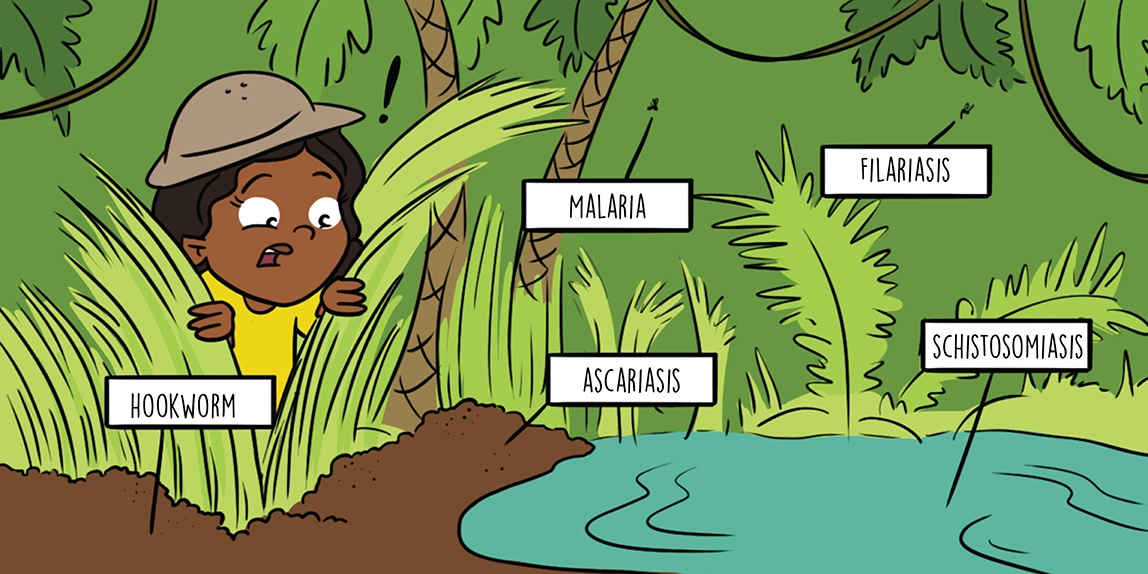

In Africa, home to 70% of the 38 million people living with HIV globally and 50% of new infections reported in 2023—most of which occur among young women and adolescent girls—the struggle to access PrEP is an ongoing challenge. Real-world implementation has been hampered by challenges such as sustainable funding for national PrEP programs, retention in care, stigma, and a lack of awareness. Despite these challenges to the broad-scale implementation of PrEP globally, this intervention, which is highly effective when available, has prevented hundreds of thousands of new HIV infections since it first emerged.

A new era of long acting injectable PrEP

In 2021, the FDA approved Cabotegravir as the first long-acting injectable antiretroviral drug for PrEP. Administered intramuscularly every eight weeks, Cabotegravir has been shown in randomized controlled clinical trials to be superior to oral Truvada for PrEP in both cisgender MSM and cisgender women for preventing HIV infection. The results of the PURPOSE-1 trial bring with them the promise of a second long-acting injectable option for HIV prevention. These injectable options are not only highly effective but also offer the unique benefits of flexibility and discrete use, which are essential for overcoming some of the most significant barriers to real-world implementation.

However, like with oral PrEP, the challenges of cost and equitable access for those who need these interventions the most, must be addressed if they are to achieve their full potential. In the United States, accessing long-acting Cabotegravir comes at a staggering cost of $23,000 per year, compared to the more reasonably priced $300 per year for oral PrEP options, which now have generic forms. As a result, many individuals who wish to use injectable PrEP find that their health insurance is not always willing to cover the added cost.

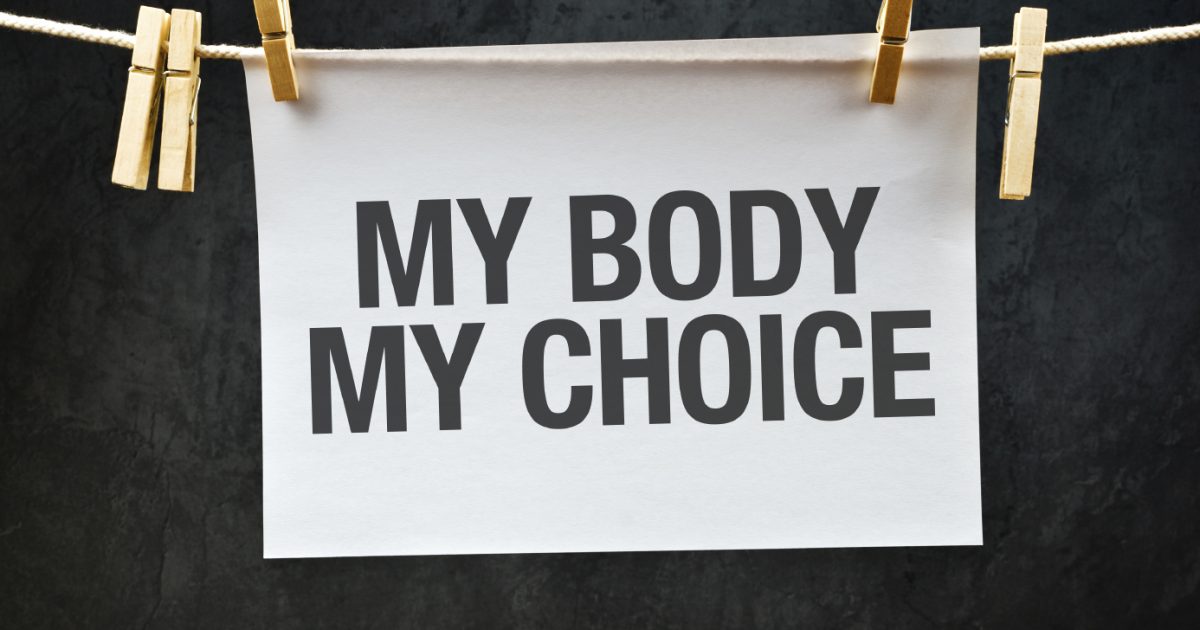

In South Africa it’s taken the sustained advocacy of tireless activists to make the cost of Cabotegravir for PrEP more affordable for African countries and importantly, accessible to African women. ViiV, the company that manufactures Cabotegravir, has renewed its commitment to “non-profit” pricing for the drug and is providing doses to support the PEPFAR initiative to expand PrEP access in Africa in 2025. It is worth noting that this compromise “non-profit” pricing although a great starting point, will need to come down significantly for broad scale access and implementation to be feasible across the African continent. PrEP is undoubtedly highly effective, but it only works if people take it. Having options ensures that there is a PrEP solution that fits the unique needs of each person. In rural communities in Africa, for example, people often have to travel long distances to access health services, making regular trips to a health center for medication refills and monitoring challenging. Women and adolescent girls disproportionately affected by new HIV infections do not always have autonomy and control over their sexual and reproductive health and having choices is even more crucial for this group. Long-acting options hold the promise of circumventing some of these barriers.

Cautious optimism amidst uncertainties for the future

As the HIV community embraces the exciting news about Lenacapavir for PrEP, many questions around pricing for African countries and the availability of generic formulations remain unanswered. The current cost of HIV treatment with Lenacapavir in the United States is estimated at $42,250 per year, a similar pricing for PrEP will make accessing the drug a challenge even for individuals living in the wealthiest countries. The history of the HIV epidemic has been marred by the constant tussle between innovation and equitable access to the newest tools to fight the spread of HIV and reduce its negative impact of communities around the world. One of the darkest moments of this checkered past is the 10-year delay it took for African countries to gain access to life-saving antiretroviral therapies after these drugs first became available in Europe and North America in the mid-nineties. This delay was largely attributed to the cost of these medications and patents that limited the manufacturing of generic formulations and led to millions of avoidable deaths from complications of HIV.

Some skeptics may argue that the urgency of providing HIV prevention tools and a variety of options is secondary to ensuring access to treatment. Or that highly effective oral PrEP options are sufficient and we should focus of expanding access to these instead of funding more expensive injectable drugs. In reality, giving equal priority to all the strategies we have for both prevention and treatment is essential to ending the HIV epidemic. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) reduces HIV levels in the blood of those living with the virus to undetectable levels, making it impossible for them to transmit the virus to others. Additionally, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with a daily oral pill or with long acting injectable drugs is 98-100% effective in preventing HIV acquisition and, adherence is most optimal when people have the freedom of choice. With these tools, we now have the capability to significantly interrupt HIV transmission and drive new infections globally toward zero. But promise alone is not enough and the last 12 years of PrEP existing have taught us that even our sharpest tools can’t accomplish much if they remain locked in the toolbox.

Only time will tell how well we have learned the lessons of the past and how strong our resolve is to end this epidemic once and for all. For now, I celebrate this important milestone and eagerly anticipate the publication of the PURPOSE-1 study details. I also hold on to the dream of a future where every new HIV transmission is easily prevented, regardless of whether someone is a 30-year-old MSM person living in San Francisco or an 18-year-old young woman in a country in Africa. This dream is closer to becoming a reality but only if we are intentional in ensuring that those most likely to benefit from these new drugs have access to them without further delay.

Written by BK. Titanji

Previously published on substack: https://bktitanji.substack.com/p/lenacapavir-a-game-changer-in-hiv

:focal(1269x729:1271x727)/origin-imgresizer.eurosport.com/2021/06/06/3147503-64505788-2560-1440.jpg)